The ancient Mayan culture rested soundly at the pinnacle of South American cultural significance in many renowned disciplines, such as engineering, art, and mathematics. There is, however, one area that the Mayan culture mastered that is often overlooked or completely misunderstood; this involved their practice of sophisticated agriculture.

The homeland of the Maya was by no means a perfect environment conducive to large-scale agricultural practices. The areas in which they inhabited were often fraught with stony soil, extensive areas of marshy wetlands susceptible to rising sea levels, storms, and droughts. Yet, even with these odds stacked against them, the Mayan culture applied engineering and adaptive measures to mitigate many of these threats and create a burgeoning agricultural society.

Maize and “The Three Sisters”

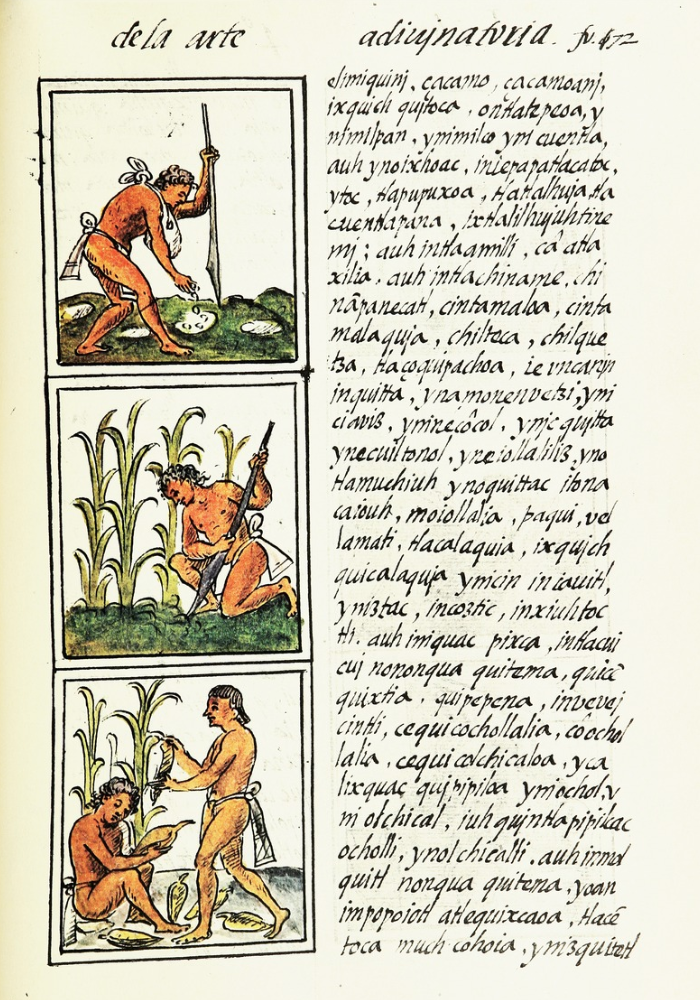

Of the various crops needed to sustain a large and productive population, one of vital importance was maize. Just as this crop became a staple of other well-established cultures throughout Mexico and North America, it was at the center of food production for the Maya. Other notable staples included beans, squash, and chile peppers, but maize was the most versatile and could be implemented in a variety of ways. Among its methods of preparation, maize could be boiled and mixed with lime and peppers, creating a dish with a consistency similar to oatmeal that became a dependable staple food. Maize was also utilized in the production of various flatbreads and tortillas which were easily made and preserved, allowing them to be distributed over large areas.

Maize was so revered by the Maya that it had its own god, Yum Kaax (Yum Caax) the God of Corn (Maize). This God was a passive entity, who in turn was dependent on the rain god Chac as well as the charity of humans who brought him water as needed. In return, he produced maize for the consumption and use of the obedient Mayan culture.

How was it that these early inhabitants of Central America managed to create such abundant resources? Often as with modern agricultural practices, patches of forest would be cleared for large-scale harvesting operations. This type of approach was not in the best interest of long-term sustainability, as the method of slash-and-burn would have to be implemented in order to rejuvenate the soil after generally only two years of crop production (on average, these fields require five to eight years to rebound for further planting). This often led to the multiple crop planting practice of growing maize, beans, and squash (known as “the three sisters”) together in the same field plots. The squash would cover the ground, and beans could use the corn stalks to grow up for support and the maize would be the central crop for mass production.

Wetland Farming

Being that much of the Mayan culture resided in or near wetlands, it was imperative to find ways of making use of such normally formidable terrain for crop production. The Maya approached this seemingly unconquerable task by building up fields and introducing irrigation canals. As the Mayan farmers dug canals through the wetlands and swamps they would pile the excess soil along the sides of the canals, creating inner fields. On average, this would raise the fields along the canals up by as much as four feet in height. Crops were then planted on these fields, preventing waterlogging of the roots of the plants, and thus providing a suitable area for plants to flourish.

The canals also acted as a haven for a multitude of water plant species. At various times throughout a season, the Mayan farmers would remove the plants to maintain water flow in the canals and then use the plants as fertilizer in the fields increasing and extending the growing season. This helped supplement the dry fields and provided a key component in maintaining a steady and dependable food source for the Mayan people, regardless of the city center location.

Raised planting beds and canal farming were but a few ways the Maya accomplished sophisticated agriculture. Another well-documented method they used was terrace farming. Mostly present in the mountainous areas of the Mayan empire, terrace farming allowed for maximum use of hilly otherwise useless agricultural land. By creating terraces on steep hillsides, the farmers were able to create an ideal drainage situation; this would also greatly reduce water runoff and erosion of soils, much in the same way the raised bed canals could be used to irrigate terrace farms.

There is still much debate over what caused the decline of the great and revered Mayan culture, with some pointing to a significant loss of available food as the culprit. We know that, for an extended period of history, these forward-thinking and adaptive progenitors of agriculture were able to provide for the masses that inhabited their cities, villages and cultural outreaches.

With the aid of satellite imagery and other modern tools, these canals and other cultural features are beginning to shed new light on the extent to which these masterful artisans utilized elaborate engineering to conquer the wild.

Jason Pentrail is a writer, researcher, and podcaster who holds an undergraduate degree in environmental science and a graduate degree in environmental management. His environmental knowledge combined with a love for archaeology, anthropology, and cultural studies provides a unique set of skills when researching and conducting field surveys and excavations. He can be reached at jason@sevenages.org.