It’s a story that’s as old as time… and the problem is that it may not be entirely true.

Discerning historical truth from narratives left to us by ancient cultures has long presented issues for scholars seeking to write about the past. For instance, many would argue that at least some of the mythology from around the world was inspired by real people and events that once transpired. The retelling of stories over time, conflated with fantastic elements and fictional tropes that convey deeper truths about the human psyche, builds mythology onto such narratives; hence, the stories that trickle down to us over the centuries are quite different from what history would actually have shown.

There are, however, other reasons information from the ancient past may not be all that it seems: this, in part, has to do with the way various cultures relied on propaganda to put a favorable spin on how future generations would see the past.

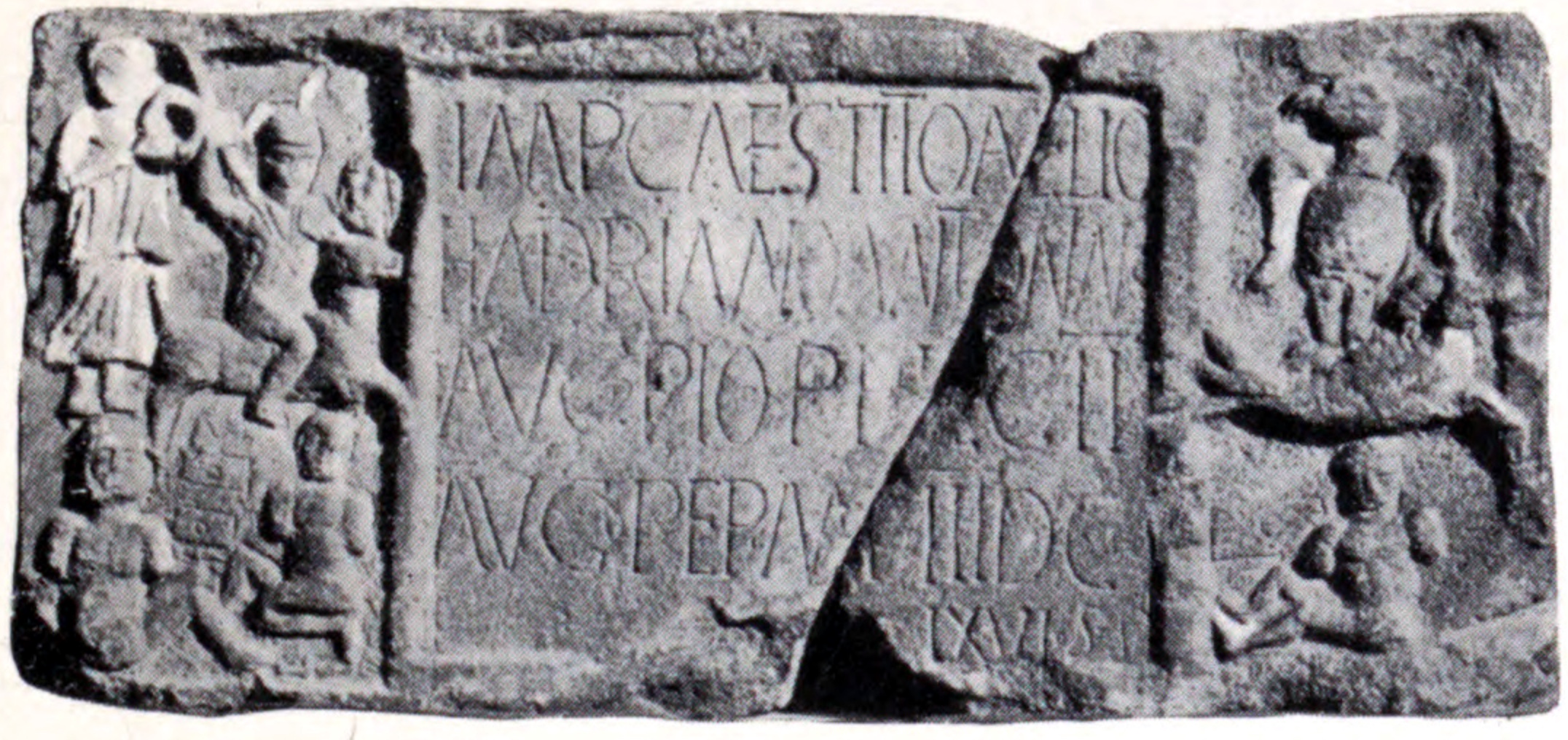

Archaeology recently reported on such a find in Scotland, where ancient Roman artisans used a blend of propagandized versions of the empire’s military exploits, paired with vivid use of color to embolden narratives featured on the famous Antonine Wall:

The Roman builders of the Antonine Wall used vibrantly painted sculptures as a propaganda tool to convey Rome’s superiority over native Scottish tribes. When the wall was built in the mid 2nd century A.D., sculpted blocks depicting Rome’s military exploits were periodically embedded into it at strategic locations. X-ray and laser technology has now shown for the first time that they were originally finished with red and yellow paint, which would have enhanced their visual impact.

William Kelly Simpson summarized it best in his 1982 essay, “Egyptian Sculpture and Two-Dimensional Representation as Propaganda,” where he noted the obvious propagandized nature of early Egyptian art, particularly as it portrayed the Pharaohs:

It is self-evident, but almost universally overlooked, that Egyptian art in many of its categories is propagandistic. Statuary, two-dimensional representation, and both elements in the decorative arts may communicate a message and attempt to persuade, publicize, or influence the beholder’s attitude. The seated statues of Rameses II in front of the temple of Abu Simbel are part of the translation of a temple pylon with statues to a rock temple, Yet they dearly serve as a signpost directed to the southerners of Rameses’ and Egypt’s might.

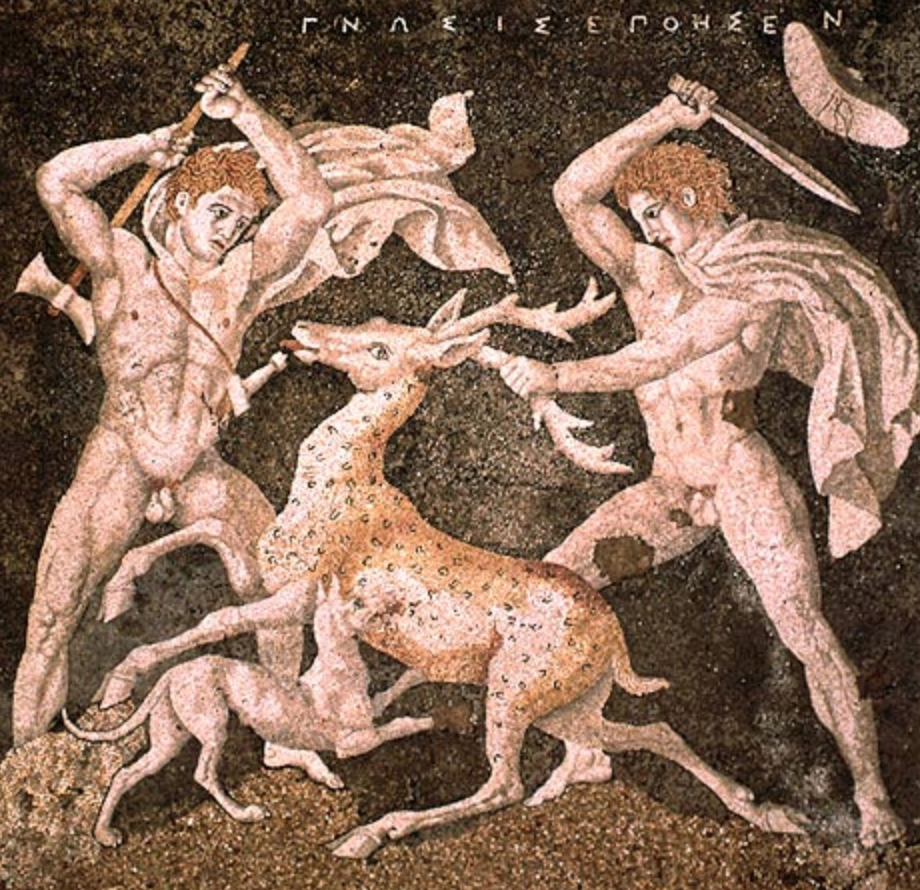

Instances of propaganda also can be found in ancient Greece, Macedonia, and Persia, namely under the influence of Alexander the Great. In an effort to work around stipulations imposed by the League of Corinth in the repatriation of some 20,000 Greeks, Alexander used propaganda in the early 300s to “deify” himself, becoming christened the son of almighty Zeus. Alexander produced currency and commissioned architecture, sculptures, and other media which emphasized his new deification, replacing all imagery of the mighty Hercules with his own likeness.

In his book Propaganda and Persuasion, Garth Jowett writes of the Macedonian leader’s propagandist efforts that, “Alexander was the first to recognize that to maintain cohesion and control over his vast empire, such propaganda symbols could serve as a constant reminder of the various subjugated populations just where the center of power resided. These strategies are still widely used today.”

French philosopher Jacques Ellul, writing in his well-regarded work Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes, instructed us on the issue in saying that, “To be effective, propaganda must constantly short-circuit all thought and decision. It must operate on the individual at the level of the unconscious. He must not know that he is being shaped by outside forces… but some central core in him must be reached in order to release the mechanism in the unconscious which will provide the appropriate–and expected–action.”

As history has shown, the use of propaganda over the last several centuries, and even into modern times, has borrowed heavily from such ancient practices. To be effective, the appeal of propaganda is one which must not only transcend the ages but also manage to effectively shape our attitudes about the past through its influence.

SOURCES:

- Archaeology, (Magazine) July/August 2018.

- “Egyptian Sculpture and Two-Dimensional Representation as Propaganda” by William Kelly Simpson. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 68 (1982), pp. 266-271 (link here)

- Propaganda and Persuasion by Garth Jowett

Micah Hanks is a writer, researcher, and podcaster. His interests include historical research, archaeology, philosophy, and a general love for science. He can be reached at micah@sevenages.com.