“The War in the West was won,” Adolf Hitler proclaimed shortly after the Nazi’s victory in their campaign against the French in May of 1940. By June 25, France had surrendered to the Reich, while Britain held steadfastly to their refusal to seek peace agreements with Germany. Thus ended a series of early military operations by the Western Allies against the German Reich that, until this time, had been only of sparing significance; this had prompted U.S. Senator William Borah to note in late 1939 that, “There is something phoney about this war.” Now, there was no question regarding the authenticity of the conflict.

Had it not been for the German strategic bombings of England and Northern Ireland that Germany launched beginning a few months after France’s surrender, Hitler may have gone so far as to attempt a full-scale invasion of Britain. In fact, plans for what had been dubbed “Operation Sealion” had been in order at one time, and ultimately postponed for a target date of September 24, 1940. However, it was eventually withdrawn completely in favor of what became known as the Blitz, during which London would sustain heavy German bombing each night for nearly two months.

History has shown the flawed approaches in Hitler’s oversight of the War. Had he allowed his generals to manage the conflict, rather than trying to do so on his own, there remains the possibility that history could have followed a very different (and unfortunate) path. However, the flaws in the Führer’s governance had become apparent early on, even among certain groups within The Reich.

Rudolph Hess, Hitler’s deputy and third in command, was no exception among those who eventually began to find flaws in his leader’s judgment. Famous for his surprise solo flight to Scotland in May 1941, Hess later admitted the trip had been conceived “shortly after a conversation with the Fuhrer in June 1940,” just prior to Hitler’s initial formulation of Operation Sealion. Published exchanges between Hess and Hitler would eventually illustrate that Hess “had grave doubts about carrying on a war against the British,” painting Russia as the greatest perceived threat to Germany at the time. This opinion was no doubt formulated with good reason; by the end of the War, Russia’s presence in the conflict would ultimately prove instrumental in Hitler’s defeat, and Germany’s eventual surrender. By April 1944, Soviet forces had swept into Berlin, and the Reichstag had been secured and captured by month’s end.

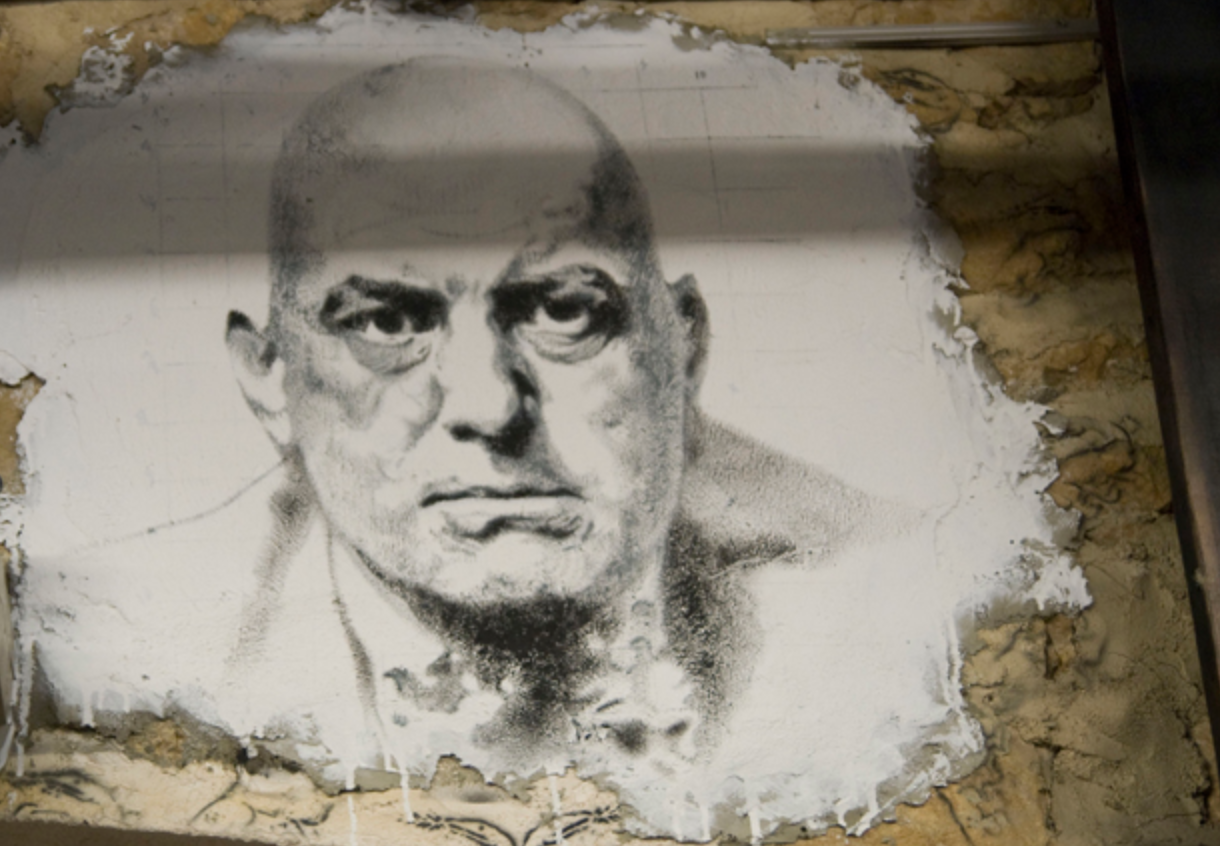

Lost in the aftermath of the War itself, as well as such pivotal historic events as the subsequent trial at Nuremberg are the more enigmatic qualities that can be attributed to Rudolph Hess. Following his late-night flight to Scotland in 1941, Hess was captured, interrogated, and ultimately found to suffer from amnesia and psychosis, prompting Winston Churchill to assert that Hess had been, “a medical and not a criminal case, and should be so regarded.” Thus, his sentencing at Nuremberg resulted in life imprisonment, rather than death. Hess served a term of incarceration for the remainder of his life, dying in 1987 at Spandau prison. And yet, many questions remain about the Deputy Führer, and perhaps more importantly, what circumstances may have led to his otherwise seemingly erratic decision to fly all alone to Scotland, under the presumption that peace-talks somehow might have ensued. Strangely, some sources may indicate there is an occult connection underlying the entire operation, which may have supplied a subversive influence aimed at luring Hess into engaging such odd behavior.

British author and researcher Ellic Howe, primarily known for his books on occultism, had actually served Britain’s Political Warfare Executive during World War II, exploring the potentials for such things as psychological warfare, forgery techniques, and general exploitation of the enemy’s hidden idiosyncrasies through the use of information and propaganda. Howe was recruited by British secret services and became involved in a number of operations regarding Nazi interest in the occult, which eventually formed the basis for a number of books he would author on the subject. According to Howe, in 1932 the Nazis founded an astrological study group called Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Astrologe; in keeping with such esoteric interests, Nazi minister of propaganda Joseph Goebbels would also go on to appoint a department of occultism, formed around the moniker of Astrology, Meta-psychology, and Occultism and referred to thusly as the “AMO.”

Regarding Nazi occult interests, among all the high-ranking Nazis, it might be assumed that Rudolph Hess had seemed the most impressionable. Even Hess’s own description of his first meeting with Hitler revealed how he felt his life was forever changed, following their introduction in a beer hall in Germany in 1920. Hess described feeling “as though overcome by a vision” while observing Hitler’s charismatic offerings; by 1940, this “vision” that Hess had seemed to maintain had progressed into a sense that he was now destined to fulfill some “greater purpose” in the War on behalf of Germany. Whatever his full intentions may have been, or the mental state underlying it, Hess seemed poised for action.

German General Karl Ernst Haushofer, who had mentored Hess several years earlier in the study of politics, stated his own feelings about Hess’s unusual state of mind around the time of the Deputy Führer’s flight to Scotland. As recorded by Dr. Rainer Hildebrandt, Haushofer later would indicate that “Hitler’s astrological aspects were unusually malefic” shortly before Hess flew to Scotland. “Hess interpreted these aspects to mean that he personally must take the dangers that threaten the Führer upon his own shoulders in order to save Hitler and restore peace to Germany.”

In essence, Hess had felt that all manner of servitude to his leader, the visionary who by grace had shared his dream with him, was justified. This formed what very nearly could be likened to the sorts of manifestations of psychological servitude between master and student, culminating over time throughout a variety of significant series of events. Hess had, in fact, literally worked as transcriptionist during Hitler’s period of incarceration in 1924, following the failed Beer Hall Putsch; though imprisoned, Hitler’s stream of thoughts were dictated to Hess, and would later form the basis of the infamous treatise Mein Kampf. There was also the fact that, in a very real sense, Hess had feared the repercussions of ongoing conflict. Of his specific motives for his historic solo flight, Hess’s wife had quoted him saying the following:

My coming to England in this way is, as I realise, so unusual that nobody will easily understand it. I was confronted by a very hard decision. I do not think I could have arrived at my final choice unless I had continually kept before my eyes the vision of an endless line of children’s coffins with weeping mothers behind them, both English and German, and another line of coffins of mothers with mourning children.

Regardless of what circumstances contributed to Hess’s devotion to the idea of coming alone to England, his actions resulted in a failed attempt at contacting supposed Anglo-German Nazi sympathizers, and after crash landing his plane in Scotland, he was captured, interrogated, and later imprisoned.

This is one half of the story, at least. The rest deals with an odd set of circumstances being enacted by the British Royal Navy during this same critical period, in which spies, secret agents, and even some degree of sorcerery had been attempted… all in the effort to secure victory against the Hitler and the Third Reich.

The Secret Agent

Interestingly, word that Hess would attempt his epic solo-flight had, according to some sources, already reached British intelligence agents in England. On the particular afternoon in question, a peculiar memo had appeared in the hands of a young Commander in the British Royal Navy, having arrived from an inside source within Germany. “Now this is what Hess proposes to do,” the message read. “He wants to fly to England alone.” The man pouring over this intriguing message had been none other than thirty-two-year-old Ian Lancaster Fleming, who later would author the famous novels of spies and adventure featuring secret agent 007, otherwise known as James Bond.

British writer Donald McCormick, who worked alongside Fleming at the foreign desk of the Sunday Times and later penned one of his biographies, maintained that Fleming’s inside contact had been a peculiar—and perhaps even enigmatic woman named Vanessa Hoffman. McCormick claimed he was briefed about the situation by Fleming later on, but was allegedly urged, “not to breathe a word of it” while Fleming was still alive. Fleming met Hoffman in Germany prior to the War, and with her knowledge of obscure social circles and a penchant for gathering information, she continued to serve as a conduit for leaks filtered to Fleming by spies and various informants infiltrating the Reich. Hoffman, though well connected, was no spy however; “Bill Findearth”, later revealed to be an intelligence agent named William Otto Lucas, had been the insider that brought her word that Hess was becoming restless. Networking with an anti-fascist network in Switzerland, as well as a handful of “moles” directly within the Gestapo, Lucas had obtained word that Hess might possess noble aspirations to enter peace talks, and had thus passed this information along to Hoffman.

According to McCormick and others, several of the War’s most sensitive details at the time were said to be obtained through this secretive chain of command, complete with an intelligence informant to the United States named Helga Stultz who worked in a room adjacent to Hitler’s office at the Berghof, his home in the Swiss Alps. Through his various information sources, William Lucas had managed to gather obscure bits of information, which eventually began to outline a rather bold idea; British Intelligence might be capable of exploiting, of all things, the strange occult interests that the Nazis appeared to maintain with such gusto.

It was already known in various intelligence circles that the Nazis may have had a strong penchant for occult sciences such as astrology, as well as secret societies that emphasized aspects of pagan ritual. Such strange bits of “crypto-history” caused a surge in interest in the subject of Nazi occultism within the decades that followed the war, with such books as Pauwels and Bergier’s The Morning of the Magicians hitting the bookstore shelves by 1960. But during the actual years of conflict, few intelligence bodies among the Allies had seemed to give much serious thought to the idea that the Nazis might be manipulated in some way by cashing in on their occult fascinations.

William Lucas, well aware of this apparent lack of interest, even suggested that the United States, who also had been receiving information from Lucas and his informants, might oblige the situation. However, Vanessa Hoffman, still serving as the liaison between Fleming and Lucas’s networks, had also been introduced to occult studies such as astrology in Germany nearly a decade earlier, in addition to sharing certain aspects of this interest with Fleming. Thus, Fleming himself had already taken a bit of a liking to various esoteric matters; one might speculate that a personal interest in such things could have inspired his eventual decision to pursue this strange tactic, having said that he, “decided to be the ‘someone else’ who might effectively exploit the idea.” The plan yet to unfold would become very much a labor of Fleming’s own undertaking, as official backing by agencies such as MI5 had not existed. Fleming’s interest in the matter, however, had been shared by at least one other prominent MI5 agent and friend, Charles Henry Maxwell Night, who later served as inspiration for the character “M” in Fleming’s James Bond novels.

While the Allies had indeed hoped to stave off an attempt at invasion by Hitler, many of Winston Churchill’s stronger military activities would later fall under criticism. This was especially the case with the 1945 bombings of the German city of Dresden toward the end of the war, in which a majority of the casualties had been civilians. Fleming, on the other hand, had been seeking more peaceful (though subversive) tactics early on, and thus the appeal of luring Nazis for purposes of espionage had obviously struck a chord.

The Sorcerer

Vanessa Hoffman’s occult interests, and the exposure she gave him along these lines, may indeed have first piqued Fleming’s own interest in the occult, but rather strangely, it was Maxwell Knight who had direct prior involvement with one of England’s most notorious occultists, the infamous Aleister Crowley. Crowley himself had worked as an informant during the war, much like Hoffman, and after being introduced to Fleming, the two were purported to have dined together a number of times at the Cavendish Hotel. It was Rosa Lewis, owner of the exclusive establishment at 82 Jermyn Street (which, its worth noting, was very close to a residence Crowley had at the time) who claimed that she had actually served Crowley and Fleming on a number of occasions in 1941. During these dinnertime talks at the stately Cavendish, the beginnings of an alleged wartime project, referred to later by Fleming as “Project Mistletoe” (a reference to the mythical character Balder of Valhalla), began to formulate precisely how occult influence over the Nazis might be used to Britain’s advantage.

According to McCormick’s biography on Fleming, this eventually resulted in the completion of an elaborate magical ritual in Ashdown Forest, in which Crowley, joined my Maxwell Knight and, of course, Ian Fleming, dressed an effigy made to resemble Hess; the ensuing ceremony had been intended at invoking the restless Hess by magical means; however, the sole testimony to this event ever having transpired can be attributed to the late Amado Crowley, who had claimed, in addition to being Crowley’s illegitimate son and protégé, that he had literally been present at the ritual itself. While there is little doubt that Knight, Fleming, and Crowley had indeed shared involvement with regard to intelligence operations during the war, little supporting evidence exists for the so-called “fireworks display” said to have taken place in Ashdown Forest.

Indeed, far more likely than the occurrence of bizarre rituals is the simple fact that Crowley, being renowned for his own occult interests, had simply been the best candidate for providing official consultation on astrological matters to British intelligence. With regard to the use of horoscopes as a medium of propaganda and misinformation, British journalist Ellic Howe’s 1982 book The Black Game detailed how he had been recruited by British Intelligence during World War II, for purposes of fabricating horoscopes that would be sent directly to Nazi strongholds, where subscriptions of a popular esoteric magazine called Zenit were already being sent. Additionally, subversive information regarding the supposed existence of an underground Anglo-German organization known as The Link was also floated through various channels, which included the Zenit horoscopes. The process was described thusly by Maxwell Knight’s biographer Anthony Masters:

Fleming briefed an astrologer, via a Swiss contact, also an agent, to infiltrate Hess’s occult circles in Germany. This he successfully did, ensuring that Hess was given the picture he and Knight had conceived, that of an influential band of plotters who wished to bring down Churchill and the government and negotiate peace with Germany. The message was passed to Hess via a fake horoscope.

The Capture

Again, history shows that the attempts at subversively urging Hess to make his strange solo flight must have been successful, to some degree. On the evening of May 10, 1941 at about 7 PM, Hess left Augsburg in a Messerschmitt BF 110D, and was eventually shot down that evening flying over Scotland. Hess parachuted from his plane, and landed near Floors Farm, Eaglesham, injuring his ankle in the process (some accounts describe Hess being arrested by a farmer, armed only with a pitchfork, as depicted in one news-reel of the time). “I decided to fly (to England) shortly after a conversation with the Fuhrer in June 1940. The delay was caused by difficulties in obtaining a machine and long-range equipment as well as unfavorable weather conditions,” Hess later said of his trip. Meanwhile, back in Germany, Hitler’s response to the Hess solo-flight had been anything but supportive; the Nazis soon launched what became known as the Aktion Hess, involving the arrest of literally hundreds of people in Germany who had fallen under suspicion of treasonous activities.

Not surprisingly, a number of the arrests made during that time had been astrologers. Hess’s own astrological advisor, Ernst Schultestrathaus, had denied having given any information that may have influenced Hess, though he was imprisoned nonetheless on the grounds that he had advised Hitler’s deputy to make the May 10th flight. The Aktion Hess had been further justified by Joseph Goebbels, who described that Hess had indeed fallen under the influence of astrologers during a period of what Goebbels referred to as “failing health”. Hess, it is said, was very troubled when became aware of such reports, and that the Fuhrer himself had even labeled him publicly as a madman.

But even supposing that Hess had made the decision to engage London in peace talks all of his own accord, with no interest or urging from British intelligence via magical rituals or phony horoscopes, we find here again that Aleister Crowley figures into the story once more. Fleming had apparently urged British Intelligence to allow Crowley, with his own obvious prowess as an occultist, to interrogate the imprisoned Hess. A personal letter from Crowley, related by Fleming biographer John Pearson, stated that:

If it is true that Herr Hess is much influenced by astrology and magick, my services might be of use to the department in the case he should not be willing to do what you wish.

Brigadier Roy Firebrace (who, as it turns out, had been the first president of the Astrological Association of Great Britain) was employed during the interrogation instead, due in part to the multitude of strange, esoteric symbolic aspects that were coming forth in ramblings of a noticeably disturbed Rudolph Hess.

And yet, as strange as the entire Hess affair had been, one final curious detail emerges regarding Fleming’s involvement in the alleged attempt to lure the famous Nazi to England. In a 1940, book written by Fleming’s brother, Peter Fleming, titled The Flying Visit, Adolph Hitler is cast as the visionary who leaps into a plane and flies to England. In the story, Hitler parachutes down and is apprehended by a British agent, after which peace talks then ensue with his captors. Of course, this odd work of fiction was published several months before the sordid Hess affair. And yet, we must ask: could Peter Fleming’s story have somehow influenced his brother’s attempts at actualizing the strange set of circumstances?

This wasn’t the case at all, according to Peter Fleming, who fervently denied the rumor until his death, calling it merely “a new legend about my brother”. Regardless, the entire story is rife with peculiar circumstances, and of course, strange synchronicities. Whether or not Ian Fleming and The Great Beast 666 had indeed played a significant role in luring Hess to England will remain a mystery. What cannot be denied, however, is that both men had nonetheless conspired to bring about the events almost precisely as they came about, and Hess was indeed successfully captured. Perhaps, if nothing else, at least one famous wartime master of spies, along with his sorcerer acquaintance, would have enjoyed thinking they were indeed the masterminds behind the whole affair.

SOURCES

1) Pearson, John. The Life of Ian Fleming. Jonathan Cape, 1966.

2) Masters, Anthony. The Man Who Was M: Life of Charles Henry Maxwell Knight. Wiley-Blackwell. November, 1984.

3) Evans, Dave and David Sutton. “The Magical Battle of Britain: Fighting Hitler’s Nazis with occult ritual.” Fortean Times, September 2012. http://www.forteantimes.com/features/articles/4435/the_magical_battle_of_britain.html

4) McCormick, Donald. 17F: The Life of Ian Fleming. Dufour Editions, 1994.

5) Churchill, Winston. The Second World War Volume III: The Grand Alliance. London: Cassell & Co. 1950.

6) Pauwels, Louis and Jacques Bergier. The Morning of the Magicians. Destiny Books. December 9, 2008.

Micah Hanks is a writer, researcher, and podcaster. His interests include historical research, archaeology, philosophy, and a general love for science. He can be reached at micah@sevenages.com.