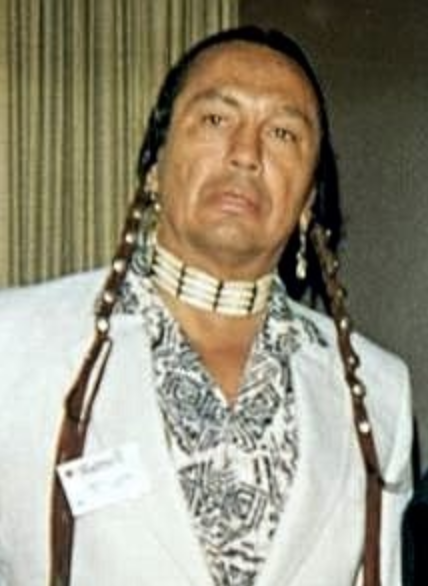

Russell Means was more than a leader, and by many accounts, more than a man: he was a living example of the struggle of the First Nations people.

Means fought against the violations of Native civil rights and stood for justice, pride and the traditions and cultural heritage of North America’s indigenous people. A leader, politician, actor, speaker, and activist, Means was a vibrant example of the pride held by the First Nations people; in many ways, he was the very definition of defiance against the system, and what it can accomplish.

Means was born in 1939 on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. His father was Hank Means, an Oglala Sioux, and his mother was Theodora (Feather) Means, of the Yankton Sioux. When Russell was a toddler the Means family moved to California, where in 1958 Russell graduated from San Leandro High School. After graduation, he continued his education at Oakland City College and Arizona State College.

Russell was driven to focus his attention on the plight and struggle of not only the Sioux people, but of all tribal nations of the United States. He began his work at Cleveland’s American Indian Center where he met Dennis Banks, co-founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM). It was during these early years that Russell embarked on some of his most renowned activities that would go on to garner national attention.

On February 27, 1973, Russell and other activists occupied the site of Wounded Knee, the infamous site of the slaying of natives by U.S. soldiers in 1890. Through this, Means gained international attention and acclaim, but not without consequence; it also landed him on many government watch lists.

In 1974 Means began to receive harassment from the FBI, and was brought to trial on a dozen different criminal suits in which he represented himself and won an acquittal in all twelve cases. That same year, Means was elected by all of the elders of the Lakota Sioux Nation to be the permanent trustee of the International Indian Treaty Council. This was a great responsibility, as Russell would now be charged with establishing an office at the United Nations in New York City.

In 1977, Means assisted in creating the first International Conference pertaining to the sovereign rights of North, Central and South American Indians in a United Nations-sponsored event. 1978 saw Means participate in the “Longest Walk,” in which Native Americans walked across the U.S. from San Francisco to Washington D.C. At the time, this was the largest single-day peaceful demonstration ever to occur in Washington D.C. and led to the end of all anti-Indian legislation in Congress.

1979 saw a brief interlude in Russell Mean’s activism, as he was arrested for a police riot that occurred at the Sioux Falls courthouse. Means was charged with “Riot to Obstruct Justice” and was sentenced to 4 years in prison, of which he served one year before being released on parole.

While Russell would be known in many circles as a staunch activist, he also achieved fame in other disciplines that included acting and politics. In 1992, Means starred as the character Chingachgook in The Last of the Mohicans. That same year, Means led the Colorado AIM in a peaceful demonstration that ended the 500th Anniversary of the discovery of America by Columbus parade. Means also made an unsuccessful bid for President under the Libertarian Party in 1987, losing the nomination to Ron Paul.

Russell Means passed away on October 22, 2012, leaving behind a legacy and influence that carries on today. His wife, Pearl Means, is also an activist and, like her late husband, remains an influential and positive figure within the Native American community. Through their combined vision and desire for equality and justice for tribal people, Russel and Pearl Means stand out among many of today’s civil rights and minority leaders.

Jason Pentrail is a writer, researcher, and podcaster who holds an undergraduate degree in environmental science and a graduate degree in environmental management. His environmental knowledge combined with a love for archaeology, anthropology, and cultural studies provides a unique set of skills when researching and conducting field surveys and excavations. He can be reached at jason@sevenages.org.