It was late 1942, and the future officer in charge of the Hanford nuclear site on Washington’s Columbia River, Colonel Franklin T. Matthias, was high above Washington State with two DuPont representatives. As recounted in S.L. Sangers’s Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of World War II Hanford, Matthias later remembered, “I thought the Hanford site was perfect the first time I saw it. We flew over the Rattlesnake Hills up to the river, so I saw the whole site on that flight… I called General Groves from Portland, and told him I thought we had found the only place in the country that could match the requirements for a desirable site.” Only a short time later, the riverside property was selected as the official site for the United States’ new plutonium production facility.

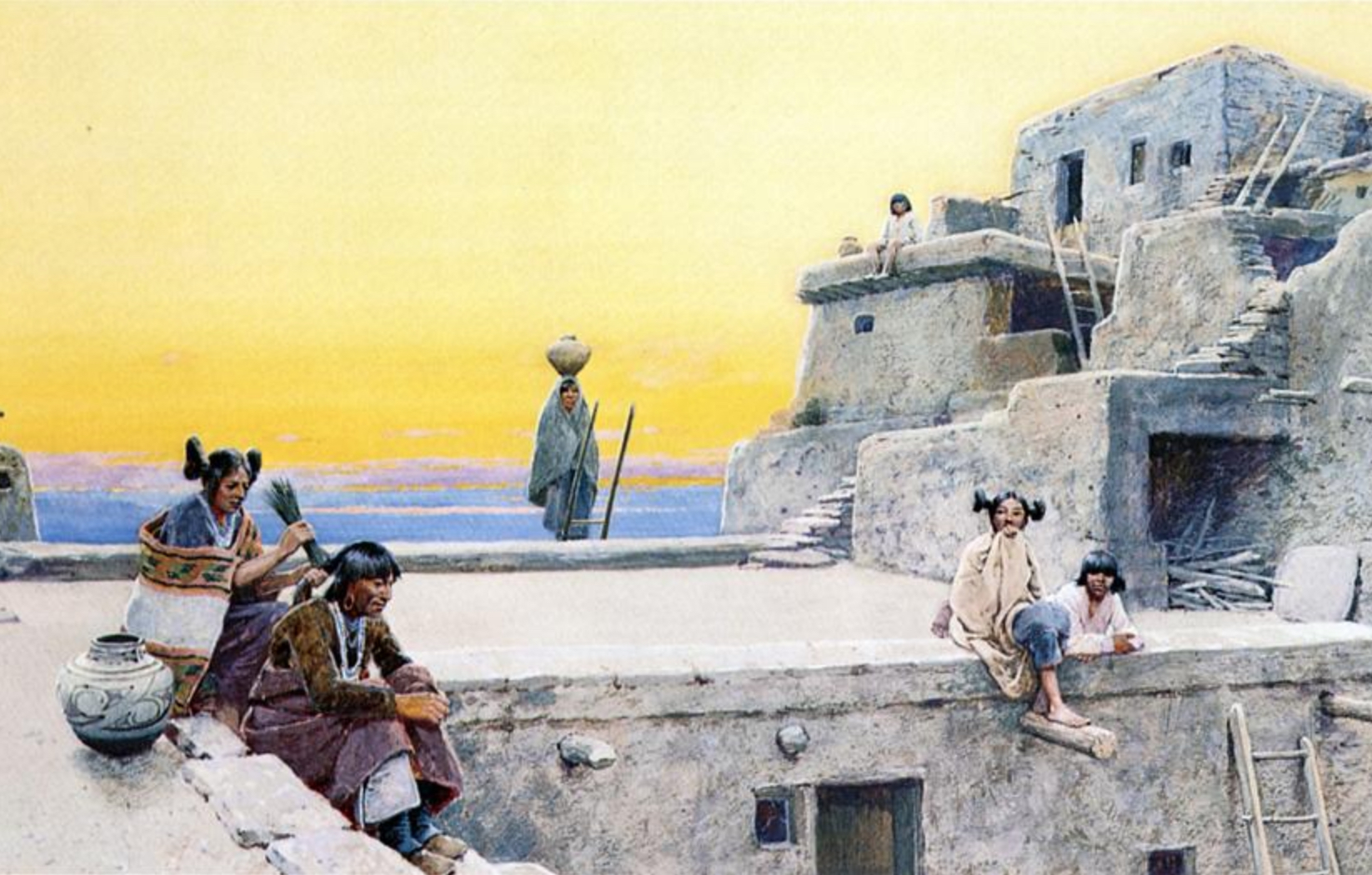

The Hanford Site has a long history, dating back well into the time before white settlers moved into the area. The shrub-steppe desert that is Hanford was once home to several different tribes of Native Americans. The land itself, and the fact that it borders the Columbia River, made for incredibly versatile living areas ripe for hunting, fishing and the rigors of daily life for these tribes.

Among those who called the Hanford region home were the Yakama Nation, Nez Perce, and ancestors of the Wanapum people. Others, according to hanfordproject.com, were the Confederated Tribes of the Colville and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation. According to nwcouncil.org the local tribes once had several fishing camps along the shoreline, such as Tah-Koot and Wy-Yow-Na located on the south shore near present-day Locke Island. At the Hanford site today there are still many artifacts, burial sites and remnants of the Native American inhabitants from the past and present.

In the Mid-1800’s pioneers and settlers began to spread out through the west, and developed settlements along the mid-portion of the Columbia River. Soon, small towns began to spring to life, accompanied by farms and cattle ranches. This type of settlement would be present at the site until 1943 when the War Department decided to relocate several different portions of the Manhattan Project to this part of Washington State. That same year, residents in the areas of White Bluffs and Hanford were forced out of their homes and farms with only 30 days notice, receiving only a small monetary payment for their trouble; many of the evicted landowners would not see a financial settlement until after the war ended.

According to the Department of Energy, the original site for this portion of the Manhattan project was to be located at the Clinton Engineer Works at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. After in-depth discussions with atomic scientists including J. Robert Oppenheimer, it was determined that due to the hazardous nature of the project, and the very real possibility of contaminating nearby Knoxville with radioactive material, that the project should be moved further west to a more remote area. With this in mind, many areas of the nation began to be searched and evaluated for the strict needs determined by the Army Corps of Engineers for the world’s first plutonium production facility.

Among the requirements listed by the Corps was an isolated area with a considerable amount of water and electricity. Regions of Colorado, Oregon, and California were also considered. Ultimately one requirement that was paramount was the site had to have access to electricity generated by one of the newly constructed hydroelectric dams located in the western United States. These included Boulder, Shasta, Grand Coulee and Bonneville.

According to the Department of Energy, Hanford was one of the largest procurements of land handled during the war, with approximately 400,000 acres being utilized. Within a year, the site was transformed into a major military and industrial complex. One reason for the vast amount of land was the desire to have the production process areas separated by large distances for safety purposes. The plutonium production reactors B, D, and F were separated by a minimum of 1 mile. The three separations plants were also a mile apart and 4 miles from the reactors. Ultimately the project would encompass more than 560 miles of government condemned land, along with the eviction of 1,500 residents including a large amount of Native Americans.

With the development of an atomic bomb as the eventual goal, little time was wasted, and production of plutonium was quickly underway. Having first been created at the Oak Ridge facility in 1940, plutonium was still in its infancy when it began large-scale production at Hanford.

Plutonium is an artificially created element. According to the Department of Energy, “it is a transuranic radioactive chemical element created through the absorption of neutrons within the nuclei or uranium atoms that have been subjected to neutron bombardment through the uranium-238 fission process.” After going through a complicated series of transmutations, plutonium-238 is created with a half-life of 24,000 years.

By 1943, the site was locked under a veil of secrecy, with intense security measures being implemented. In a letter to General Leslie Groves on June 29, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated:

“I am writing to you as the one who has charge of all the development and manufacturing aspects of this work. The fact that the outcome…is of such great significance to the nation requires that this project be even more drastically guarded than other highly secret war developments.”

Being that this site was so large and employed some 51,000 people that secret was monumentally hard to keep. None the less those still living in close proximity to the site had no idea what was being created there.

It was August, 1945, when the secret of Hanford would be revealed to the world, as atomic bombs were dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, effectively hastening the end of WWII. While the war was now only a sorrowful memory, the new postwar stockpiling of nuclear weapons had begun; thus, it was only a short time before the United States and the Soviet Union would become adversaries. This fading relationship was directly responsible for the increase of nuclear development in weapons and innovative delivery systems in both countries.

As the newly named “Cold War” continued to develop, the late 1940s and early 1950s saw major congressional allocations for expanding the U.S. nuclear arsenal. This, of course, resulted in a major increase of plutonium production at the Hanford site. Hanford would remain the primary production facility until 1953 when the Savannah River site was completed in Georgia. Between 1947 and 1955, the Atomic Energy Commission added five new reactors at the Hanford site. The area would continue to expand from 1947 to 1949, again during the Korean War 1950-1952, and again under President Eisenhower from 1953-1955, with a major spike in production occurring between 1956-1964.

In addition to the plutonium production, the grim and alarming experimentation phase was also part of the Hanford story. By the 1950s, extensive classified radiobiological studies and experiments were being conducted on humans, aquatic species, plants, and various animals. Hanford was home to an aquatic center, a biology lab, and an eventual radiotoxicology center. Among these various experiments and studies included monitoring the thermal and chemical effects of reactor discharge on salmon, and the effects of radioiodine on sheep. There were also experiments conducted on volunteer inmates and even accidental exposures of various sorts to Hanford scientists.

With this much production and waste being created, it comes as no surprise that the Hanford site is recognized as one of the most environmentally devastated sites in the United States. The release of radioactive waste into the atmosphere, ground, and water table have all occurred, with specific impact on the Columbia River. Often claiming that national security was at risk, often the public was not informed when such harmful releases occurred. According to the Washington State Department of Health, “it is estimated that nearly 2 million people were exposed to radiation through atmospheric releases or through Columbia River water from 1944 to 1972.”

According to the Department of Energy’s own reports, during the production days of the Hanford site, millions of tons of solid waste were created along with hundreds of billions of gallons of liquid waste. The solid waste, which can be anything from broken equipment, to contaminated employee clothing, was buried in the ground in various pits and trenches. The liquid wastes were disposed of by pouring them into the ground, or into trenches and holding ponds. There were inevitable accidental spills as well. The liquid generated during the process of plutonium extraction from uranium fuel rods was placed in underground storage tanks. It has been noted that some of the records describing precisely what waste went where were recovered, while some of the spills along with the associated volumes went undocumented. Today, much of the transuranic solid waste has been packaged up and sent to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, where it will be buried.

The Hanford site is a key part of the history of both the United States and of warfare. It is also a testament to the price to be paid by the environment, and often by unsuspecting citizens. The cleanup of the site began in 1989 with the last reactor being shut down in 1987. Since then, six of Hanford’s nine reactors have been “cocooned” or demolished. 879 facilities have been demolished as well, 1,339 waste sites have been remediated, and 18.3 million tons of soil and debris have been moved to an engineered landfill. The entire cleanup list can be accessed at the Hanford.gov website.

The legacy the site leaves behind includes what are referred to as “downwinders” from the site, who argue that the region’s overwhelming number of thyroid diseases and various types of terminal cancers are most likely the results of the Hanford site’s plutonium production activities. A study conducted in 2002 called the Hanford Thyroid Disease Study stated, “researchers found that the occurrence of thyroid disease in the study group was about the same as has been reported for other populations.” Many of the citizens in the area disagree, especially those of Native American heritage, who still subsist off the land at a higher rate than the general population.

It is safe to say, regardless of the safety assessments and studies over the years, that there has been an environmental impact at Hanford. A heightened sense of alarm is only natural among residents in a location that has seen such high-level radioactive pollution.

While cleanup efforts continue, much of the undocumented waste–whether solid or liquid–can not, and will not be retrieved effectively, making this region a public hazard for many decades to come. Both noble, and tragic, Hanford was the result of desperate men at a desperate time; a dark period in American history the likes of which we hope will not occur again.

Jason Pentrail is a writer, researcher, and podcaster who holds an undergraduate degree in environmental science and a graduate degree in environmental management. His environmental knowledge combined with a love for archaeology, anthropology, and cultural studies provides a unique set of skills when researching and conducting field surveys and excavations. He can be reached at jason@sevenages.org.